The Medieval period in Ipswich reflects the wider experience of England under Norman rule. It was a time of re-organisation, development and centralisation which affected the ancient towns of England in different ways. For East Anglia, resistance to new power structures led to a dramatic decline in the wealth and power of the region as a result of the punitive actions of Norman lords. Following the Norman conquest and a period of adjustment, Ipswich seems to have developed a new urban character, although the archaeology currently leaves many questions unanswered.

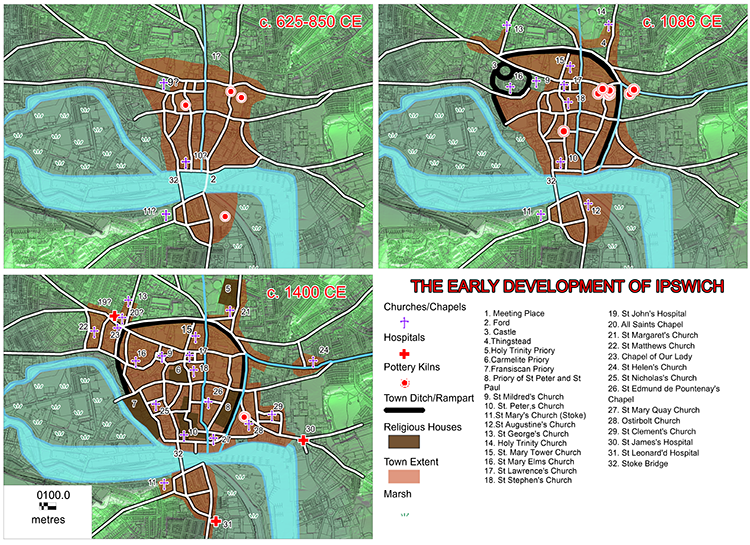

Image: The development of Ipswich from the 7th to the 15th centuries.

The Norman Town (1066-1200 AD)

The Domesday Book of 1086 decribes the town and indicates a severe decline after 1066. By the time of writing, 328 of Ipswich’s burgess plots lay waste and there were only 110 burgesses left who could afford to pay their customary dues to the King. By the middle of the 12th century, Ipswich was no longer a primary town in the country - the possible result of competition from the network of towns which had been founded across East Anglia during the late Saxon period.

This decline is well-represented in the archaeological record. On the major sites of Buttermarket/St Stephen’s Lane and Foundation Street, buildings go out of use in the late 11th/early 12th century and the sites are not redeveloped until the 13th century. Some of these buildings were burnt down, which preserved a wealth of construction detail and in some cases the contents of the buildings. The most likely cause of this sudden decline was William the Conqueror’s successful suppression of a rebellion against him by the earl of East Anglia in 1075.

The Domesday Book entry for the Half-Hundred of Ipswich lists thirteen churches in 1086. Two were in the wider Borough: St Botolph, Thurleston and one in Stoke with no dedication mentioned (probably St Mary’s). Eleven were in the urban core: St Peter’s (2), St Augustine, St Mary’s (2), St Stephen, St Lawrence, St Julian, St Michael, St George, and Holy Trinity. The foundation date of these churches remains unknown and six of them are now gone. Only one, St Augustine’s in Stoke, has been excavated and found to be of eleventh century construction.

The town also had a castle, constructed and destroyed in the twelfth century. Its location is unknown and various sites have been suggested. The most likely of these is the area bounded by Civic Drive, Westgate Street and Elm Street but there is no archaeological evidence to date.

The Medieval Town

During this period, five new churches were built serving the suburbs: St Margarets, St Matthews, St Clements and St Helens on the fringes of the urban core, and St John’s in the hamlet of Cauldwell.

In the urban core, two of the major excavations (Buttermarket/St Stephen’s Lane and Foundation Street/School Street) coincided with the precincts of medieval friaries and ground plans of both the Carmelite and Dominican friaries were recovered. Little is known about the other monastic establishments: the Greyfriars, largely destroyed by the development of that name, the Priory of St Peter and St Paul, east of St Peter’s Church, and the Holy Trinity priory, on the Christchurch Mansion site. Some wall fragments and burials have been excavated in all three.

Further burials have been excavated in the churchyards of St Mary Quay, St Margaret’s, St Nicholas, St Lawrence, St Clement’s and the chapels of Our Lady of Grace, in Lady Lane, and St Edmund de Pountney, in Lower Brook Street.

In addition, cemeteries of lost churches have been partially excavated in Fore Street (the cemetery of Osterbolt), Westgate Street (unknown) and Berners Street (St George’s Church) and the Leper hospital of St James, at the junction of Fore Street and Back Hamlet. A second Leper Hospital, St Leonards, is known to have been sited on the Wherstead Road but no traces have yet come to light.

Pottery kilns excavated in Fore Street show that pottery production continued during this period, producing Ipswich Glazed ware from c.1270-1325 AD.

Few medieval houses have been excavated apart from some 13th-14th century clay and timber buildings along Key Street, and these were on sites which have not been properly analysed and reported as the developer-funders were unable to complete the project.

In the wider Borough, little has been found of the known hamlets of Wicks Ufford, Wicks Bishop, Brookes and Stoke. Excavation of the moated site in Holywells Park (Wicks Bishop) has demonstrated a medieval date and watching briefs in the Brookes Hall area have produced medieval pottery and building materials. Pottery found during test-pitting of the allotments at Maidenhall may also indicate a small medieval hamlet or farm in Stoke. Burials and wall footings have also been found of the lost church of St Botolph at Thurleston.

Late Medieval/ Early Post Medieval (1450-1600 AD)

Most excavated sites in the urban core have produced evidence of this period. Merchant houses, constructed in masonry, have been excavated on the sites along College Street and Key Street. Little is known about Wolsey’s College which took over the medieval priory of St Peter and St Paul, but substantial walls including a brick turret have been excavated east of St Peter’s Church.